![]()

Radical Prostatectomy

|

| |

|

This section describes the procedure involved in having a prostate operation for cancer of the prostate

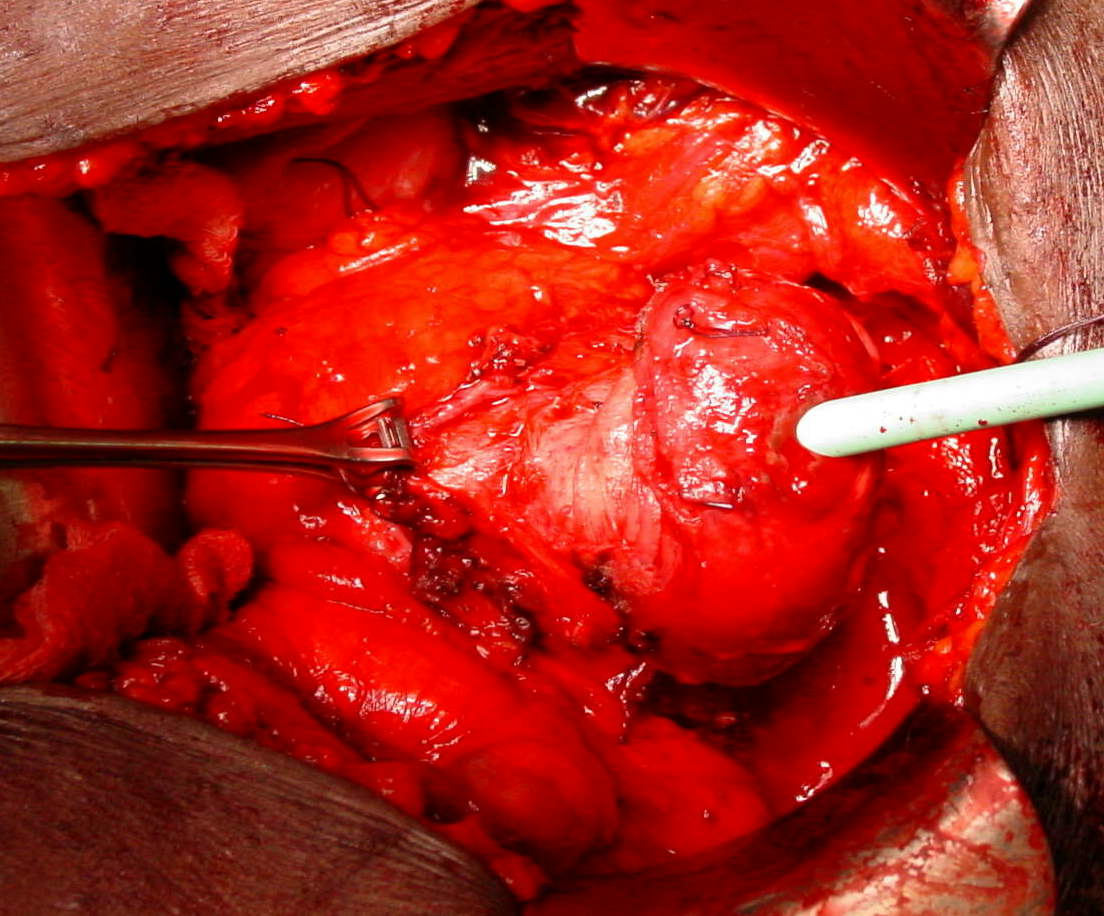

This image shows the prostate being raised out of the pelvic cavity during traditional open prostatectomy. You will have discussed the reasons behind having the surgery, which are to remove a cancerous prostate in its entirety, aiming for complete cure of the tumour. | |

![]()

How is the operation performed?

At King's College Hospital we were pioneers in carrying out this operation laparoscopically (via keyhole surgery), usually using robotic camera assistnace. Most men stay only one night in hospital.

The procedure is carried out by making a small puncutres in the lower abdomen, and removing the prostate using telescopic instruments, finally enlargin one of the puncture wounds to make a hole through which the prostate is removed.

After removal of the prostate, the neck of the bladder is sewn to the urethra (water pipe) using dissolving stitches. A drainage tube is left beside the bladder to drain any blood or secretions within the first twenty four hours, this is removed prior to hospital discharge. A catheter (urine drainage tube) is required for a week or so after the operation to rest the tissues which have been joined. This tube can be removed either at home or in the outpatients department.

The skin is closed with either a dissolving stitch or one which is removed at the same time as the catheter is removed: this will be discussed with you.

The prostate which has been removed is sent to the laboratory for extensive evaluation to assess the state of the tumour and obtain a more accurate prognosis. (This is usually carried out by Dr Debbie Hopster, our urological pathology consultant at King’s College Hospital) We may ask for permission to use some of the prostate tissue in our research studies: this would not affect the operation or your care in any way.

Before and after removal of the catheter you will be asked to carry out pelvic floor exercises to strengthen the muscles around the pelvis. This should speed your return to continence, which may nonetheless take several months.

While this is a major operation, the risk of serious side effects is lower than before due to improvements in technique. There may be bleeding at the time of surgery: the necessity for blood transfusion with laparoscopic surgery is less than one in twenty. Anticoagulant treatment is given to reduce the risk of venous thrombosis following the operation. The risk of serious chest infection is reduced by advances in anaesthetic techniques.

Obviously there is some pain and discomfort after the operation although with modern painkillers this is rarely a severe problem: patients are up and about the day after the operation.

Many men who have this surgery will become incapable of getting a spontaneous erection as the nerves to the penis are either removed to ensure removal of the cancer or may be stretched during surgery. Happily this problem, which also usually occurs after radical radiotherapy, is now treatable so that a couple can continue their physical relationship after this type of surgery.

However because the semen producing organs have been removed the orgasm will be changed. The orgasm will be "dry" and may be less intense and focussed than before although this is rarely a major problem as long as men know what to expect. Some men describe the orgasm as similar to how they imagine a female orgasm. The operation will make men sterile since an internal vasectomy is carried out.

Most men will have a little incontinence compared to before the surgery, particularly on strenuous exercise. This is rarely a major bother. However, about one man in thirty will have severe troublesome incontinence necessitating constant use of pads to catch urinary leakage. Again this is a treatable problem.

Some incontinence is normal in the weeks and months following surgery and can be helped by the frequent use of pelvic floor exercises. Patients are seen by our Continence Nurse Specialist before and after discharge.

Urinary symptoms caused by a blockage of the flow of urine by the prostate will usually be overcome by the operation although occasionally the bladder may be troublesome for a few months: this can be treated by bladder calming medicine. In about one in twenty cases a narrowing of the join between the bladder and the urethra can occur and this may require a minor procedure to stretch it up, usually with no long term implications on the continence.

Fatigue is common after any procedure and it may take two or three months to fully recover physically and mentally from the stress of major surgery. One should be careful not to try to do too much in this period and a gradual return to normal activities is essential: you will be advised on this as you recover. Heavy lifting should be avoided for eight weeks after the surgery, and you should avoid driving for around three or four weeks.

We usually see men a couple of weeks after the catheter is removed to make sure that the continence is improving and to discuss erection treatment if appropriate. A PSA test will be done after about three months . Thereafter follow-up is usually every three to four months in the first year, then increasing gradually to a yearly check-up and PSA blood test.

Some doctors in the UK would argue that treatment is not necessary for men with localised prostate cancer. For men with a life expectancy of ten years however this seems unnecessarily nihilistic, since we know that a certain number of years of life is lost if early prostate disease is not treated. There are now good tables showing the risk of death or disease prgression in untreated men, and these can be compared with the likely outcome of treatment in a given individual. For men with low risk disease, active monitoring or consideration of trials of focal therapy will be considered.

Options apart from Surgery include radical radiotherapy and the newer form of interstitial radiation which involves placing high dose radioactive seeds into the prostate (brachytherapy).

The benefits of external beam radiotherapy are that it does not require anaesthesia and is less likely to cause incontinence: it involves around six weeks of daily visits for treatments. With brachytherapy the treatment is given during two general anaesthetics several weks apart. Althoughthe long term risks of incontinence are a little lower than with surgery, men with urinary symptoms will usually find these get worse for some months after the treatment. While it was previously though that radiotherapy tehcniques had a low risk of impotence, this is no logner certain. Clearly a potential disadvantage of radiotherapy is that the prostate is not removed and thus cannot be submitted to the pathologist for accurate staging. It is also the case that after radiotherapy the PSA level may be a little more difficult to interpret than after surgery, and that for patients with "higher risk" tumours surgery seems to have more of a suruvual benefit. Most experts would take the view that the choice of treatment is for the patient to make, but that in young men or where the tumour is thought to be definitely confined to the prostate surgery is the preferred option.

Our attitude us that patients should consider all the options and consult widely before making a decision. Each patient must be considered as an individual when choosing the correct approach.

Copyright (c) 1999-2009 GH Muir. All rights reserved.

mail@london-urology.co.uk